OPINION: Banned, Not Gone—Can Bangladesh’s Awami League Spark Peaceful Change?

Ultimately, it raises questions of profound importance: Is it possible to transform a nation without resorting to bloodshed?

The movement to ban the Awami League was hardly an isolated event; rather, it traced its origins to the student unrest that erupted in July 2024. Initial grievances focused on education policy, persistent corruption, and the burdens of economic hardship, but the agitation rapidly escalated into violence.

The coalition of dissent widened as Islamist organizations and right-wing groups joined the mobilization, their rhetoric coalescing with that of newly formed student parties, National Citizen’s Party. The public discourse became saturated with serious allegations: both the Awami League and its student affiliate, the Chhatra League, faced blame for violent reprisals and the deaths of hundreds during the previous year’s protests. Over time, the demonstrators’ demands intensified. Calls emerged for the party to be designated a terrorist organization and for its leadership to be prosecuted before the International Crimes Tribunal.

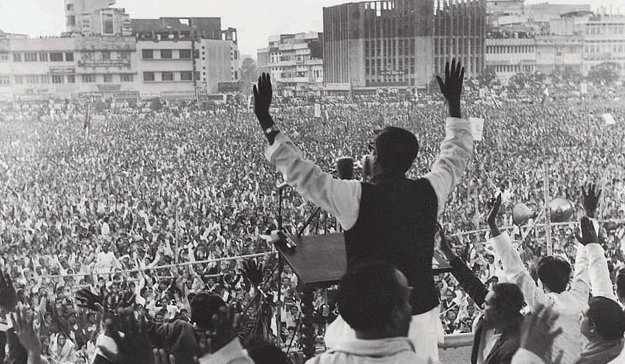

This pressure culminated in a significant government response. Chief Advisor Muhammad Yunus declared the party banned under the Anti-Terrorism Act, pledging that the prohibition would remain until all charges had been legally examined. While many protesters celebrated this outcome, the broader atmosphere in Dhaka remained charged with anxiety and uncertainty. The Awami League, a party whose history is deeply intertwined with the founding of Bangladesh in 1971, now found itself the subject of condemnation and legal scrutiny by the very populace it once liberated from Pakistan.

A Unique Protest to ban

The demonstration against the Awami League rapidly escalated into a deeply unsettling display of extremist fervour. Islamist groups, including those reported to have connections with organizations such as Al Qaida, became highly visible among the protesters. Notably, Mufti Jashimuddin Rahmani—a cleric widely recognized for his radical ideology—publicly brandished the flag of Islam, a symbol that, after years of association with violent acts, now carries significant and troubling connotations.

Representatives from Hizb ut-Tahrir, Hefazat-e-Islam, and associates of Rahmani with criminal convictions gathered, their collective presence casting an unmistakable pall over the city’s atmosphere. The demonstration fragmented with Jamaat E Islami and Islami Chatra Shibir; both groups chanted slogans like, “No Awami League in the land of Nizami, no Awami League in the land of Golam Azam,” referencing individuals convicted of war crimes in 1971 as if they were figures worthy of admiration and they owned Bengal. Another segment of the crowd escalated the rhetoric further, openly issuing death threats: “Catch and slaughter Awami League one by one.”

The environment became saturated with hostility—a manifestation not of peaceful political dissent, but of incitement to violence. At this point, the gathering ceased to resemble a lawful protest; rather, it devolved into a perilous spectacle in which the boundaries between legitimate calls for justice and extremist violence were dangerously obscured, seemingly fuelled by both state endorsement and radical zeal.

The Controversial Ban

The international community observed the unfolding events with marked concern. Human rights organizations, like Human Rights Watch characterized the ban on the Awami League as arbitrary, raising questions regarding the government’s intentions—was this a pursuit of justice, or an attempt to suppress dissent? The United Nations previously expressed alarm over banning what it described as diminishing civil liberties, while India openly voiced apprehension on democratic future as a response to the ban.

The government justified its actions under the pretext of national security. Yet, this raised a crucial issue: who defines the parameters of security when the opposition is excluded from participation? Many questioned the legitimacy of a democracy that outlaws its oldest political party. The ban’s reach extended beyond politicians—it affected students, women, and entire communities. Such measures prompted debate over whether this constituted justice or amounted to collective punishment.

Tensions escalated throughout Dhaka; the disappearance of protestors and the retreat of supporters into clandestinity reflected the climate of fear and uncertainty. While some framed the crackdown as a necessary purge, most observers interpreted it as symptomatic of broader societal anxiety.

International actors, including foreign governments and NGOs, called for transparency, adherence to legal norms, and meaningful reforms. The interim government promised stability, yet the cost of such “order” remained ambiguous and contested.

This situation provokes reflection: Is this the outcome for which Bangladesh’s founders struggled in 1971, or does it represent a cyclical return to past traumas under new guises? When national symbols are suppressed and political expression is stifled, what remains of democratic governance?

Critics drew a distinction between punishing an organization and addressing criminal behaviour, underscoring the dangers of conflating the two. The world now watches closely, questioning who ultimately benefits from the absence of opposition, and who might be targeted next.

What’s next for Awami League?

The recent ban is undeniably severe, and the authorities’ response has been rigorous, even unyielding. Yet, as reported by Voice of America, public sentiment does not overwhelmingly align with the ban. Notably, in district bar elections, lawyers affiliated with the Awami League performed unexpectedly well. However, in many districts the interim Government forced them not to participate. Online surveys continue to indicate that the party retains substantial support, frequently leading in popularity. So, is this a conclusion, or merely another episode in a protracted political journey?

Historically, the party has confronted similar obstacles. After 1975, the Awami League operated clandestinely but ultimately re-emerged, playing a pivotal role in the 1990 movement for democracy. At present, many of its leaders are in hiding; their residences have been ransacked and their financial assets frozen. Some face threats of violence, torture, and live under persistent fear. Nevertheless, history offers important lessons. The Awami League was conceived in resistance, matured in secrecy, and spearheaded the independence war of 1971. The critical question is whether such resilience can be summoned once again.

Arguably, this period represents one of the most formidable challenges the party has faced. Growing anti-incumbency sentiment and the ban itself are compelling the organization to reassess its strategy and reconnect with foundational principles. This moment calls for a renewed study of Mujib’s legacy, the pre-independence struggle, and the dynamics of political survival. Operating covertly, the party must reorganize, adapt, and remain patient heading for a Non-violent cultural revolution.

A non-violent cultural revolution, at its core, does not emerge through slogans or public altercations. Instead, it finds its genesis in artistic expression—music, poetry, and the collective act of remembering. Such change germinates in intimate gatherings, within the retelling of stories about figures like Mujib and the struggles of founding leaders, and in the songs that once served as a unifying force for the nation.

Both the young and the elderly revisit historical narratives, not for the sake of lamentation, but to derive lessons about resistance that is devoid of animosity. Art, within this context, evolves into a vehicle for protest, while protest, conversely, assumes the qualities of art. This form of revolution proliferates in educational spaces, in casual conversations at tea stalls, and within the quiet but resolute refusal to embrace violence. Ultimately, it raises questions of profound importance: Is it possible to transform a nation without resorting to bloodshed?

The Awami League has demonstrated a remarkable capacity for cultural and political resurgence in the past. Whether it can transform present adversity into renewed opportunity is a new challenge. Ultimately, as has so often been the case in Bangladesh, the outcome will be difficult, but the grand return is far from over.

Disclaimer: Views expressed by writers in this section are their own and do not reflect Milli Chronicle’s point-of-view.