Pashtun Nationalism and the Punjabi State: Pakistan’s Unfinished War Within

For the Pashtun people, questioning Pakistan Army’s role and pointing its misconduct in the tribal belt is to invite accusations of treason as the state did with PTM.

Pakistan’s relations with Afghanistan have plunged to their lowest point in years. The recurrent clashes across the Durand Line that divides the two countries are often framed as a dispute over the Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP), a Pashtun Islamist insurgent group which has become Achilles heel for the Pakistani state. But, beneath the surface of this conundrum lies a much older struggle that predates the Taliban and the war on terror. It is the decades long tension between Pashtun nationalism and a Punjabi-dominated Pakistani state.

The TTP is often described purely as an umbrella militant organisation. Yet it represents a fusion of Islamism and ethnic grievance and is a product of decades of marginalisation of the Pashtun heartland by a state that has alternated between military repression and strategic manipulation. To understand why the conflict refuses to end, one must revisit how Pakistan’s power structure was built on the exclusion of its largest ethnic periphery.

Pashtun nationalism did not begin with neither Afghan Taliban nor Pakistan Taliban. Its current incarnation dates to Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan, or Bacha Khan, also known as the “Frontier Gandhi,” who led the non-violent Khudai Khidmatgar (“Servants of God”) movement in British India. Bacha Khan, as a staunch secularist as an ideological commitment opposed India’s religion-based partition of 1947. However, when partition became a fait accompli, he, and others in the tribal leadership, demanded that the Pashtuns be allowed the choice of creating their own Pashtunistan (the Bannu Resolution of 21 June 1947).

In the years that followed, Bacha Khan and his followers were vilified, jailed, and banned and their demands for provincial autonomy was branded as treason by the Pakistani state which increasingly became military dominated. This set the template for how the country’s overwhelmingly Punjabi-dominated ruling establishment would treat dissent from the peripheries: with suspicion, suppression, and militarisation.

Despite extreme suppression and oppression, the legacy of Bacha Khan’s peaceful struggle survives to this day through movements like the Pashtun Tahafuz Movement (PTM) and Awami National Party (ANP) by highlighting Pakistan Army’s misconduct through enforced disappearances, extrajudicial killings and sexual violence across the tribal belt.

The PTM’s rallies were filled not with insurgent slogans but with portraits of missing persons, chants for accountability, and the insistence that their blood be valued as much as any Punjabi. While PTM has been proscribed by the Pakistani state and its leaders like Manzoor Pashteen routinely silenced, yet their demands echo the same call made nearly eight decades ago which is that of dignity, rights, and an end to collective punishment.

If history began with exclusion, it was the Pakistani military that institutionalised control. The colonial-era Frontier Crimes Regulations (FCR) that represented a draconian legal code denying tribal residents due process remained in place as recent as 2018. For over seven decades, the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) were governed this FCR that granted local tribal lords with autonomy thereby treating people treated as subjects rather than citizens.

The tragedy of Pakistan’s Pashtuns is that they have been both the sword and the sacrifice of the state being deployed in its proxy wars and displaced in its peace. Their land has been used as a laboratory for proxy wars, their people as cannon fodder for strategic depth. The Pakistani military viewed these borderlands less as communities and more as a strategic buffer.

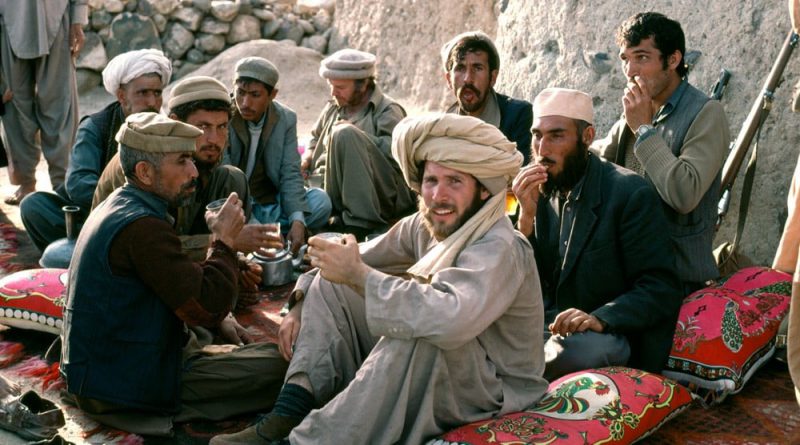

In the 1980s, during the U.S.-backed Afghan jihad against Soviet forces in Afghanistan, the Pashtun belt was turned into a staging ground for mujahideen recruitment and weapons smuggling. After 2001, it became a battleground again but this time for Pakistan’s ambiguous war on terror. While Islamabad allied with Washington, its intelligence services sheltered the Afghan Taliban, seeing them as a tool of regional influence.

Caught in the crossfire were ordinary Pashtuns. Between 2004 and 2024, according to various estimates including South Asian Terrorism Portal (SATP) and CRSS Annual reports, at least 20,000 Pashtun civilians have been killed in Pakistan Army’s anti-insurgency campaigns and militant violence between 2004 and 2024. Besides, over 4000 people were also killed in hundreds of American drone strikes greenlighted by Pakistan Army according to a report by the Bureau of Investigative Journalism.

Moreover, thousands of people were internally displaced, their homes flattened, family members disappeared, and entire villages across North and South Waziristan were razed under Pakistan Army’s counterterrorism operations like Rah-e-Rast (2009) and Zarb-e-Azab (2014). To this day, thousands remain unaccounted as victims of “enforced disappearances” with Pakistan military and its intelligence agencies as prime accused, with at least 3485 cases reported by the Missing Person’s Commission established by the Supreme Court.

As such, rather than peace, Pakistani state’s reliance on militarisation in the peripheries has only produced alienation. On ground, it reflects in the garrisoning of the Pashtun heartland with checkpoints dotting every artery and locals subjected to random searches and collective reprisals. A generation and two of Pashtuns have grown up knowing only checkpoints, recurrent curfews, and ever-present drones sounds and strikes.

If muscular policy of subjugation in their homeland was not enough, Pashtuns have long been cast as the “other” in Pakistan’s social imagination as ‘rough’ and ‘uncouth’ cousin to the so-called urbane Punjabi. This cultural stereotyping has been deeply ingrained in Pakistani cinema and literature with Pashtuns often portrayed as tribal, backward, and violent. Such characterisation has helped the state justify its decades of systemic exclusion of Pashtuns as well as normalise Pakistan Army’s misconduct.

This is also achieved by domination of the Punjabi elite within the politics and media of the country as well as the officer corps of its powerful army. While Punjab is Pakistan’s largest province by population, comprising 53 percent of its total population, it has a disproportionate share of senior military positions and federal bureaucratic positions with some estimates putting it above 70 percent In contrast, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, including FATA, has been grossly underrepresented in the corridors of power in Islamabad and Rawalpindi with less than 12 percent and 10 percent share in federal bureaucracy and officer corps of armed forces respectively.

The costs of this hierarchy are stark. KPK remains among Pakistan’s poorest provinces, with nearly 30 percent of the population enduring multidimensional poverty, which is nearly double that of Punjab. Literacy among women in former FATA tribal districts hovers below 15 percent, which is nearly three times less than KPK (39 percent) and four times lesser from women in Punjab (58 percent). Infrastructure spending per capita in KPK is a fraction of that in Punjab’s major cities. The region’s development budget has often been slashed to subsidize military operations or bailouts for state-owned enterprises concentrated in Punjab and Sindh.

Such disparities are not accidental function as the political architecture of a state that conflates security with ethnicity. For the Pashtun people, questioning Pakistan Army’s role and pointing its misconduct in the tribal belt is to invite accusations of treason as the state did with PTM. Even the merger of FATA into KPK in 2018 (25th Amendment), which was hailed as a democratic milestone has changed little on the ground. At best, it remains an annexation on paper rather than empowerment in practice.

Perhaps the darkest face of this militarised policy of the state is the impunity with which Pakistan Army conducts itself across the Pashtun heartland. For Pashtuns, the state’s “war on terror” is simply a war on being who they are and their identity often conflated with extremism and militancy. Islamabad and Rawalpindi never seem to understand that the killing of a family member, an arbitrary arrest or an enforced disappearance and every other misconduct of its military only fuel resentment and rebellion.

Detestably, Pakistan’s Punjabi-centric political and military elite often view Pashtun nationalism as an existential threat with a fear that such calls for justice and accountability might evolve into secession. Yet it is not separatism the demand for equal citizenship that drives the new generation of Pashtuns.

Islamabad’s refusal to reckon with this sentiment carries peril. The more the state relies on coercion, the more it alienates the very population it claims its own. The Afghan frontier may remain under barbed wire and drones, but the deeper frontier of Pakistan’s powerful Punjabi core and its neglected peripheries continue to widen.

Nevertheless, if Pakistan is to find stability, it will need to must start by listening to its margins be it Pashtuns, Baloch, and Sindhis, among others. But that would mean an end to its current policy of militarisation, accountability of its past actions and to the human rights violations of its military, and importantly allowing Pashtun people shape their own governance than dictating it from the garrisons of Peshawar. Until the Pashtun heartland is treated not as a frontier to be controlled but as a homeland to be respected, Pakistan’s both internal and external wars will never truly end.

Disclaimer: Views expressed by writers in this section are their own and do not reflect Milli Chronicle’s point-of-view.