Public Debate on God’s Existence in India: What Akhtar vs Nadvi Exposed

This is where the debate truly failed to meet. Nadvi spoke at the level of personal belief and moral philosophy. Akhtar spoke at the level of society, history, and institutions.

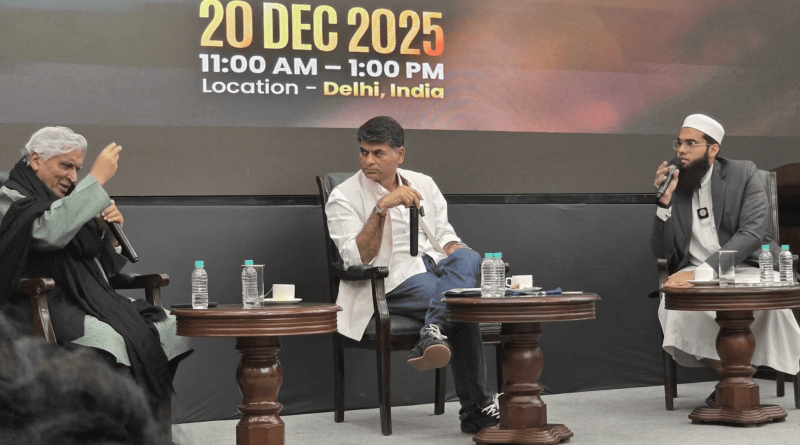

The debate between Javed Akhtar and Mufti Shamail Abdullah Nadvi, held on 20 December 2025 at Delhi’s Constitutional Club and moderated by Saurabh Dwivedi of Lallantop, was important simply because it took place. In India today, public disagreements on religion rarely reach the stage of an open, face-to-face discussion. They usually collapse long before any discussion into outrage, boycott calls, or cancellation. This debate broke that pattern.

The event also had a long and bitter history. Months earlier, Javed Akhtar had been invited by the Urdu Academy of West Bengal to preside over a mushaira. Mufti Nadvi publicly opposed the invitation and appealed to Muslims to reject the event. The controversy grew, the mushaira was cancelled, and the matter ended without closure.

Later, Nadvi announced that a debate with Akhtar would take place on December 20. That history gave the debate added weight. It was not just about God; it was also about how disagreement should be handled openly.

On the surface, the topic was simple: does God exist? But the debate quickly showed that the two speakers were not addressing the same question.

Mufti Nadvi came prepared. He spoke clearly, calmly, and with structure. His arguments were rooted in classical Islamic theology and philosophy. He used familiar lines of reasoning about contingency, infinite rigorous,moral order, dependence, and meaning. He stayed focused on the question as he understood it and kept returning to it. For many viewers including myself, and a large section of Muslims, this clarity made him appear the stronger participant.

Javed Akhtar, by contrast, relied on arguments he has repeated for years in public forums. These arguments were not necessarily weak, but they were not tailored to the debate at hand. He did not directly engage with the theological framework Nadvi was using. At times, the exchange felt less like a debate and more like a loose conversation. The difference in preparation and argument was visible.

This is why many concluded that Nadvi emerged the clear winner (I believe he had won the debate thumpingly). But the deeper problem -was not performance. It was a conceptual confusion.

Javed Akhtar’s criticism has never really been about God as a metaphysical idea. His target has always been organised religion. He opposes religion as a system of power—one that controls behaviour, enforces conformity, claims moral superiority, and often causes harm. When Akhtar speaks against God, he is usually speaking against this system, not against spirituality or inner belief.

Mufti Nadvi, however, defended a very different idea of God. He spoke of God as personal, inward, and experiential. His God was about conscience, comfort, moral grounding, and meaning. This God was not tied tightly to institutions, laws, or clerical authority. In a sense, Nadvi tried to separate God from religion itself.

Because of this, the two were talking past each other from the beginning.

Akhtar criticised a God that comes with rules, punishment, and social control. Nadvi defended a God that exists beyond institutions. Akhtar challenged religion as it functions in society. Nadvi spoke of faith as it exists in the individual heart.

This mismatch weakened Akhtar’s position in the debate. He never fully clarified whether he was rejecting God altogether, rejecting religious institutions, or rejecting the social use of religion. That lack of clarity made his arguments seem scattered.

At the same time, Nadvi’s position also has limits.

The idea of a religion-free God may work philosophically, but socially it is fragile. In real life, belief does not exist in isolation. Most people do not arrive at God through abstract thinking. They encounter God through family, community, rituals, language, and tradition. For the majority, God exists because religion exists. Remove institutions, and for most people the very idea of God becomes unclear.

Believing in God while rejecting religion entirely is possible for a small, educated, and secure section of society. It is not how belief functions for most people. Akhtar understands this reality. His skepticism comes not from metaphysics, but from observing how religion actually operates in the world.

This is where the debate truly failed to meet. Nadvi spoke at the level of personal belief and moral philosophy. Akhtar spoke at the level of society, history, and institutions. One was asking how faith should be understood. The other was describing how belief actually works.

Both positions are internally consistent. But they operate at different levels. Because this difference was never resolved, the debate became a series of parallel arguments rather than a direct engagement.

Still, the debate mattered.

It showed that disagreement does not have to lead to exclusion. It showed that difficult questions can be discussed publicly without fear. In a time when religion is often used to silence criticism and atheism is often dismissed as arrogance, this conversation—however flawed—was necessary.

More such debates are not the compulsion of the hour. A society that cannot argue openly will eventually stop thinking altogether. Disagreement, when expressed honestly and faced directly, strengthens public life far more than silence ever can.