The Khalistan Narco-Terror Syndicate: History of Violence and Its Drivers

A host of Western thinkers, security analysts, and former high-ranking officials have exposed the Khalistan movement as a violent, transnational threat.

Khalistan began as a separatist movement engineered by some disgruntled politicians who weaponised religion and exploited grievances for power, money, and control. Soon, it transformed into a terrorism project with a core foundation built on violence, terrorism, and criminal activity.

By the early 1970s, a few operatives shifted to Europe, the UK, and North America to globalise the agenda. This provided access to millions of diaspora funding, political cover, and protection under Western freedoms and asylum systems.

The core propaganda claims that Khalistani militancy emerged as a reaction to the events of 1984.

This is historically false since the “reactive militancy” narrative functioned as a cover for pre-existing violence. This article traces how Khalistan developed into a global terror-criminal network, rooted in separatist ideology, sustained by crime, and enabled by foreign safe havens.

What Popular Voices Think of Khalistan

A host of Western thinkers, security analysts, and former high-ranking officials have exposed the Khalistan movement as a violent, transnational threat. These influential figures argue that the movement has mutated into a “Crime-Terror Nexus” that endangers global security.

Michael Rubin, former Pentagon official, has compared the rise of Khalistani extremism to the early days of Al-Qaeda, warning that Western complacency today mirrors the pre-9/11 era. He argues that when states tolerate these groups as “political,” they provide cover for a growing terror threat.

Dr Paul Bullen, a PhD scholar, criticised Khalistani terrorism and exposed the hypocrisy of mainstream media, stating that even questioning Khalistan is treated as taboo. He argued that the media has consistently failed to critically examine sensitive issues such as Khalistani terrorism.

Dr Christine Fair, a leading South Asian security expert, has detailed the “Pakistan-Khalistan” connection, noting how extremist elements are utilised as proxies in a broader asymmetric warfare strategy, describing the movement as deeply rooted in militant violence.

The Hudson Institute (US-based think tank), highlights how these groups use “Human Rights” narratives to masquerade as victims while engaging in extortion, radicalisation, and the glorification of convicted terrorists like Talwinder Singh Parmar.

Terry Milewski, Senior Canadian journalist, in his landmark 2020 report, “Khalistan: A Project of Pakistan,” exposed the movement as a geopolitical pawn. He argues that the separatist cause is a “failed idea” kept alive by foreign interests to destabilise the region, rather than a genuine grassroots movement.

Peter Chalk, a RAND Corporation’s counter-terrorism expert who has lectured on the “Punjab Lessons,” has analysed the movement’s history of mass casualty attacks, specifically the 1985 Kanishka bombing, as the blueprint for modern diasporic terrorism.

A History of Khalistan-Linked Violence in India

Khalistan-aligned militancy has been linked by authorities to a decades-long cycle of violence that has left thousands of dead. Indian government estimates attribute around 12,000 civilian deaths and 3,400 security personnel deaths to insurgency and terrorism associated with Khalistan-oriented groups from the late 1970s onward.

Violence first escalated in the late 1970s, beginning with the 1978 Vaisakhi clash in Amritsar, where followers of the Damdami Taksal and activists aligned with pro-Khalistan sentiment led by Fauja Singh confronted the Nirankari sect, resulting in 13 Taksal followers and 3 Nirankari members killed.

Through the early 1980s, political assassinations and targeted killings increased, including the 1980 killing of the head of a Sikh religious group, after which Ranjit Singh was convicted. A turning point came in 1984, when Prime Minister Indira Gandhi was assassinated by her bodyguards Satwant Singh and Beant Singh, an event that triggered anti-Sikh pogroms and further radicalization.

Satwant Singh and Kehar Singh were later executed. The late 1980s saw mass-casualty attacks, including the 1987 Lalru and Fatehabad bus massacres in which over seventy Hindu passengers were shot and killed. Indian agencies attributed the attack to the Khalistan Commando Force (KCF).

In 1988, authorities reported widespread deployment of improvised explosive devices in crowded urban areas, including markets and railway stations, allegedly involving militants such as Avtar Singh Brahma of the Khalistan Liberation Force (KLF) and Gurbachan Singh Manochahal of the Bhindranwale Tiger Force of Khalistan (BTFK).

Escalation, Decline, and Resurgence

Violence persisted into the 1990s, beginning with the 1991 Ludhiana train attack, where gunmen killed over a hundred passengers, and an attack the same year on former Punjab police chief Julio Ribeiro while he was serving as ambassador to Romania.

In 1995, Punjab Chief Minister Beant Singh was killed in a suicide bombing carried out by Dilawar Singh Babbar, Balwant Singh Rajoana and Jagtar Singh Hawara were later convicted.

After a relative decline in organised militancy during the 2000s, authorities continued to report attacks involving Khalistan-linked organisations: the 2005 Delhi cinema bombings, attributed to Babbar Khalsa International (BKI), targeted theatres screening films about Punjab’s insurgency, while in 2007 a blast in Ludhiana’s Shringar cinema killed six, leading to convictions including Gurpreet Singh.

Although the overall scale of violence remained lower than its 1980s–90s peak, the 2010s saw a series of targeted killings. From 2016 to 2017, eight assassinations of religious and political figures — including Hindu leaders and a Christian pastor — were investigated by Indian authorities, who alleged involvement of Canada-based Hardeep Singh Nijjar (later designated a terrorist by India) and Raman Deep Singh.

The decade also included the 2015 Dinanagar police station attack, which killed seven. Indian officials alleged cross-border coordination between Khalistani elements and Lashkar-e-Taiba, though these claims remain disputed by some.

The 2020s have seen sporadic incidents, such as the 2021 Ludhiana court blast, where the bomber died in the explosion and investigators alleged overseas coordination involving Jaswinder Singh Multani of Sikhs for Justice (SFJ), and the 2022 RPG attack on Punjab Police Intelligence Headquarters in Mohali, with Canadian-based Lakhbir Singh “Landa” identified by police as a suspected planner.

Designated Organisations and Ongoing Concerns

India has banned several groups under the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (UAPA), stating that they have supported or carried out violent activities.

These include Babbar Khalsa International (BKI), linked by authorities to Wadhawa Singh Babbar, the Khalistan Commando Force (KCF), once associated with Paramjit Singh Panjwar, the Khalistan Liberation Force (KLF), previously linked to Harminder Singh Mintoo, and Sikhs for Justice (SFJ), led internationally by Gurpatwant Singh Pannun, who is designated a terrorist in India.

While supporters of these groups often deny involvement in violence and frame their goals as political advocacy or independence movements, Indian security agencies maintain that elements within or associated with them have facilitated terrorism or secessionist violence.

The history of Khalistan-linked militancy therefore remains deeply contested, rooted in complex political grievances, human rights debates, and the legacy of trauma experienced by many communities across India and the Sikh diaspora.

A Transnational Landscape of Alleged Khalistan-Linked Crime

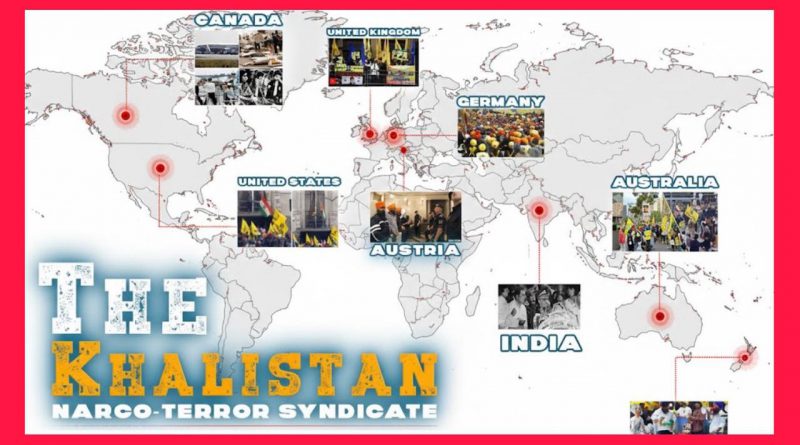

The international dimension of Khalistan-linked activity has drawn sustained attention from law-enforcement agencies across North America, Europe and the Asia-Pacific.

In Canada, the most infamous incident remains the 1985 Air India Flight 182 bombing, which killed 329 people; Inderjit Singh Reyat was convicted on manslaughter and perjury charges, while Talwinder Singh Parmar, alleged by investigators to have been involved, died in a 1992 police encounter.

Decades later, authorities continue to allegefinancial and criminal networks tied to extremist elements: intelligence assessments linked major cocaine and fentanyl seizures in 2025 narcotics investigations, including the “Project Pelican” probe, to fundraising channels for radical outfits.

That same year, Inderjit Singh Gosal of Sikhs for Justice was charged in Ontario with firearms offences, while Gursewak Singh Bal faced conspiracy-to-murder charges in the United States after being connected to the Surrey shooting and drug trafficker Ryan Wedding.

Canadian policing documents and governmental designations have repeatedly associated groups such as Babbar Khalsa International, the International Sikh Youth Federation, the World Sikh Organisation, and the Sikh Federation with extremist ecosystems; supporters of these organisations often dispute these claims, arguing they are political advocacy entities.

In the United States, concerns date back to the 1990s, when federal authorities alleged that Bhajan Singh Bhinder played a role in procuring military-grade weapons, including Stinger missiles and AK-47s, through covert channels; these claims arise largely from undercover operations and confessions that defence lawyers have long contested.

More recent cases include the 2017 conviction of Balwinder Singh, sentenced to fifteen years for providing material support in an attempted assassination plot, and the 2019 designation of Jasmeet Hakimzada as a “significant foreign narcotics trafficker” by the U.S. Treasury for an alleged heroin network spanning the U.S., U.K. and Australia.

In 2025, an FBI multi-state raid in California yielded arrests for kidnapping and weapons crimes, including Pavittar Singh Batala, alongside Dilpreet Singh and Amritpal Singh, who prosecutors claimed were tied to Babbar Khalsa International.

A wide constellation of Sikh diaspora organisations — from Sikhs for Justice and the Council of Khalistan to cultural and advocacy bodies such as SALDEF, the Sikh Coalition, United Sikhs, ENSAAF, and research or community groups like the Khalistan Affairs Centre and Jakara Movement — are frequently referenced in media or political narratives.

Many of these groups explicitly deny any association with militancy and describe themselves as civil-rights or humanitarian initiatives.

Europe, Asia-Pacific, and the Evolution of Overseas Activity

In the United Kingdom, the 1987 Dormers Wells school shooting during a Sikh religious gathering resulted in convictions for Rajinder Singh Batth and Mangit Singh Sunder, marking one of the first high-profile prosecutions linked to Khalistan militancy on European soil.

The 2012 stabbing of retired Indian general K.S. Brar in London led to prison sentences for Santokh Singh, Mandeep Sandhu, and Dilbag Singh, while legal battles over Paramjit Singh “Pamma”, arrested in Portugal on an Interpol red notice in 2015–2016, underscored ongoing extradition disputes.

Groups cited in British intelligence and government reports include the Sikh Federation (UK), International Sikh Youth Federation, the National Sikh Youth Federation, and the World Sikh Parliament, though many activists maintain these organisations are mischaracterised and are non-violent political platforms.

Across Austria, Germany and Italy, several significant cases shaped European jurisprudence on terrorism and extremism. The 2009 Vienna temple attack, where two were killed and fifteen injured during a religious service, resulted in convictions for Jaspal Singh and multiple accomplices.

German courts later convicted Gurmeet Singh Bagga and Bhupinder Singh Bhinda for a 2012 assassination conspiracy and, in Bhinda’s case, a 2016 conviction for diaspora surveillance that targeted moderate Sikh figures.

In Italy, Gurjant Singh Dhillon was sentenced in 2020 for financing actions that authorities deemed terrorist activity. European security services routinely list groups such as Babbar Khalsa International, the Khalistan Zindabad Force, the Khalistan Commando Force, and the Khalistan Liberation Force as banned under regional terror legislation.

Elsewhere, the 1985 Narita Airport bombing in Japan, which killed two baggage handlers, was linked to the same coordinated plot as Air India 182, with Inderjit Singh Reyat convicted for constructing the device.

In Southeast Asia, the flight of high-profile fugitives led to arrests: Jagtar Singh Tara, convicted in India for the assassination of Punjab chief minister Beant Singh, was detained in Thailand in 2015, while Harminder Singh Mintoo, former KLF chief, was captured using forged documents.

In Australia and New Zealand, police reports and community testimonies describe increasing vandalism of temples and intimidation within Sikh communities from 2023 to 2024, allegedly linked to cells influenced by Sikhs for Justice and campaigns around unofficial “referendums”.

Names such as the Australian Sikh Council, Royal Army of Khalistan, Sher-e-Punjab Brigade, Pure Tigers, and Azad Khalistan surface intermittently in local investigations; public records show a mixture of formal extremist designations and unverified claims, highlighting the contested nature of diaspora activism versus militancy.

Why Khalistanis Exploit the West?

USA: Offers international visibility and influence; operations gain global attention. Canada: Acts as a funding hub via trafficking, extortion, and donations.

UK: Attractive for immigrants; easier community consolidation and recruitment. Europe (general): Some countries (e.g., Armenia, Germany) have weak extradition, making it safe for fugitives.

The Pakistan Story of Khalistan Backing

From its inception, the Khalistan movement benefited from Pakistani patronage, strategic, logistical, and financial support. Since the 1970s, Pakistani actors have provided early platforms to Khalistan proponents, as it aligned with Pakistan’s long-standing doctrine of bleeding India with a thousand cuts.

Key dimensions of Pakistan’s backing: Early shelter & legitimacy: Khalistan leaders were hosted, amplified, and encouraged when they lost relevance in India. Monetary & logistical support: Funding channels and facilitation helped militants and propagandists operate abroad.

Training & coordination (1980s-90s): Militant elements received assistance that strengthened insurgent capacity. Western expansion: With Pakistani facilitation, Khalistan networks entrenched themselves in the UK, Europe, and North America, leveraging diaspora fundraising and media access. 13 Feb 2025: Ahead of the Indian PM’s visit to the White House, ISI agent Ghulam Nabi Fai was seen leading a pro-Khalistan Protest, clarifying Pakistan’s backing of Khalistan.

Terrorism in the Shadow of a Movement

Khalistan has mutated into a multi-billion-dollar transnational terror syndicate. Surviving on foreign financing, Western complacency, and Pakistan’s proxy-war doctrine.

The Four Pillars of Survival: Exporting Conflict: When relevance fails in India, terror infrastructure is shipped to the diaspora to radicalise the next generation.

Manufacturing Victimhood: To mask violence, the syndicate exploits “Human Rights” narratives to gain political cover in the West.

Terror as Visibility: High-profile strikes (like the 1985 Air India bombing or 2022 Mohali RPG attack) are used to signal strength to global donors.

The Crime-Terror Nexus: Ideology is now fuelled by Narco-Trafficking. Profits from synthetic drug labs in Canada and heroin pipelines from the “Golden Crescent” fund weapons and “referendum” logistics. Western freedoms were not the problem, their systematic exploitation was.

Treating Khalistan syndicate as “political expression” allowed it to metastasise from a fringe movement into a global terror network. When terrorism is tolerated, it does not moderate, it becomes an industry.

Disclaimer: Views expressed by writers in this section are their own and do not reflect Milli Chronicle’s point-of-view.