Sect, State, and Survival: The Asads and the Reversal of Syria’s Social Order

Regimes that prioritize power over people will eventually crumble, no matter how long they hold on.

On December 8, 2024, millions of Syrians across cities and villages celebrated what many believed was an impossible dream—the end of Bashar al-Assad’s brutal regime. For over five decades, the Assad family ruled Syria with an iron fist. But to understand how this ruthless dynasty rose—and how it ultimately fell—we must rewind the clock to the early post-colonial years of Arab nationalism and military coups.

This analysis is based on the research of Nikolaos van Dam, former Dutch ambassador and Special Envoy for Syria, as outlined in his work for The Rights Forum. As a seasoned diplomat who served in Lebanon, Jordan, the Palestinian territories, Libya, Iraq, Egypt, Turkey, and beyond, van Dam’s insights provide a rare, first-hand account of Syria’s internal transformation over six decades.

The Birth of Ba’athist Idealism

In the late 1940s, a young Alawite military officer named Hafiz al-Assad joined the Arab Socialist Ba’th Party. The party’s platform—built on secular Arab nationalism and socialist ideals—promised equality among Arabs regardless of sect or religion. This secular vision, crafted in part by Michel ‘Aflaq, a Greek Orthodox Christian from Damascus, appealed strongly to religious minorities and economically disadvantaged rural populations.

For Alawites, Druze, Isma’ilis, and Christian Arabs—communities historically marginalized in Sunni-dominated political circles—Ba’thism offered both inclusion and upward mobility. But this idealism would soon be manipulated into a tool of power centralization and authoritarian control.

The 1963 Ba’thist Coup: From Ideals to Authoritarianism

Syria’s brief experiment with Arab unity reached its climax in 1958 when it merged with Egypt to form the United Arab Republic (UAR). But the union quickly disillusioned many Syrians. Under Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser, Syrian officials were reduced to subordinate roles, sparking resentment.

By 1961, the union collapsed following a coup staged by Syrian officers, leading to the brief “Separatist Period,” a return to parliamentary governance and conservative elites. However, in the background, socialist military factions, particularly from the Ba’th Party, were organizing for a comeback.

On March 8, 1963, Ba’thist officers seized power, marking the beginning of one-party rule. Political pluralism was dismantled, and only parties loyal to Ba’thist ideology were allowed under tight control. Syria’s multiparty democracy was officially dead.

The Rise of the Secret Military Committee

Ironically, many of the Ba’thist officers who masterminded the 1963 coup had been exiled to Egypt during the short-lived UAR period. There, they formed a clandestine “Military Committee” with one purpose: to take over Syria upon their return.

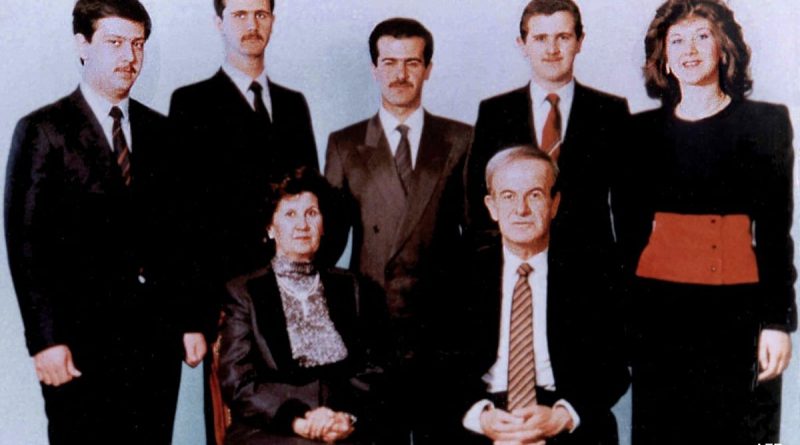

This committee was dominated by three Alawite officers—Muhammad ‘Umran, Salah Jadid, and Hafiz al-Assad. While other minorities such as the Druze, Isma’ilis, and Sunnis were represented, none held top leadership roles. What began as a coalition soon turned into a brutal contest for power.

Through successive purges, each rival was systematically removed until Hafiz al-Assad emerged as Syria’s uncontested ruler in 1970. The original Ba’thist vision of collective leadership was discarded in favor of personalized autocracy—ushering in what would become known as Asadism.

Asadism: The Cult of Personality

Under Hafiz al-Assad, a robust cult of personality developed. State media praised his every move, and over a hundred books were published in his honor. This phenomenon wasn’t unique to Syria; authoritarian regimes across the Arab world used leader-worship as a means to legitimize their rule.

What set Syria apart was the depth of sectarian entrenchment, particularly the favor shown to Assad’s Alawite sect. The military and civilian bureaucracy were filled with relatives and loyalists from his coastal hometown and surrounding villages.

Sectarian identity was not the regime’s stated ideology, but it became its operational strategy. Trust was reserved for those from Assad’s own background, feeding a system of clientelism, cronyism, and corruption.

A System Built on Loyalty, Not Merit

Following the 1963 coup, Assad and his allies purged the military of Sunni officers and replaced them with Alawites and other loyalists. This was not about ideology—it was about trust and control. The same pattern extended into civilian ministries, universities, and state-owned enterprises.

In his memoirs, prominent Ba’thist Sami al-Jundi described how rural villagers, many from Alawite and Druze regions, began flooding into Damascus. The linguistic marker “Qaf,” characteristic of mountain dialects, began dominating public discourse in government halls and tea shops alike.

Traditional Sunni elites, particularly urban merchants and landowners, were systematically replaced by newcomers from lower social strata. But while this shift appeared revolutionary, it merely exchanged one elite for another—this time bonded by kinship and loyalty rather than class or religious dominance.

Unequal Gains: Alawite Power, Rural Neglect

Despite Alawites’ dominance in government and military structures, the majority of Alawites in rural regions remained impoverished. This paradox highlighted the selective nature of regime patronage. Privilege was not granted on the basis of sect alone, but on one’s proximity to the power core—both geographically and personally.

This imbalance created growing resentment, not just among urban Sunnis but even among marginalized Alawite communities who felt betrayed by a system that bore their name but delivered no benefits.

The Final Years: Bashar’s Inheritance and Ruin

When Hafiz al-Assad died in 2000, his son Bashar—a British-educated ophthalmologist—was hastily installed as Syria’s president. Hopes for reform quickly evaporated. Bashar’s reign saw a doubling down on authoritarianism, culminating in a brutal crackdown on peaceful protests in 2011. What followed was a catastrophic civil war that fractured Syria into fiefdoms and killed over 500,000 people.

The war exposed the hollowness of the Ba’thist state. Military power was no longer sufficient to maintain legitimacy. Iran and Russia stepped in to preserve Assad’s grip, but at the cost of Syria’s sovereignty.

The End of the Asad Era

By late 2024, Assad’s isolation was complete. With dwindling Russian support, growing international sanctions, and internal dissent, the regime finally collapsed on December 8. What comes next remains uncertain, but Syrians have a rare opportunity to rebuild their nation from the ashes of dictatorship.

The fall of the Assad regime is more than a political event—it is the closing chapter of a failed 61-year experiment in authoritarian Arab nationalism, sectarian favoritism, and personal rule. The lesson is clear: regimes that prioritize power over people will eventually crumble, no matter how long they hold on.